By Lisa Rowell

Rikiyah Pryor and her mother Brenda Pryor. Photo by Amanda Muse, Soulful Photography

To better understand and appreciate Black History Month, we talked with Rikiyah Pryor, the Marketing and Public Relations Director for Citizens Bank. She is the immediate past president of the Somerset Business & Professional Women’s Club. Her mother Brenda is the acting president of the organization this year. Rikiyah is the vice president of the Kentucky Federation of Professional Business Women (KFPBW) and president of the Young Professionals of Lake Cumberland.

A history lesson

To respect Black History month, which was established in the U.S. in 1976, let’s refresh our memories about some of that history in our state.

The year was 1800. Having been recently established, a young Pulaski County, Kentucky, had a population of 3,161. According to the Second Census of 1800 Kentucky, there were 232 enslaved people in the county.

Data from the U.S. Federal Census shows the county’s population would swell to 15,831 by 1860. This number did not include enslaved people. Pulaski County would be home to 285 slave owners, 1,150 Black slaves, 180 Mulatto slaves, 18 free Blacks, and 34 free Mulattoes.1 There were 11,000 registered Blacks in Kentucky in 1860, however, according to explorekyhistory.gov, there were more than a quarter of a million enslaved people in the state.

“ I’m not saying we have to focus on the past. All I’m saying is to acknowledge it.”

—Rikiyah Pryor

All persons held as slaves within rebellious states are and shall be free…

President Abraham Lincoln issued the Emancipation Proclamation in 1863, but slavery in Kentucky would not be abolished just yet. The proclamation did not apply to enslaved people in five non-Confederate states which included Kentucky.

The 13th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, passed by Congress in early 1865, provided that, “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States, or any place subject to their jurisdiction.” Lincoln would not live to see the amendment ratified that December. Slavery legally ended in Kentucky on December 18, 1865. Federal law forced enslavers in Kentucky to emancipate enslaved people but the Amendment was not ratified in the state until the 20th century in 1976.

“Free” didn’t mean FREE

In KET’s Free Blacks in Antebellum Kentucky, Kentucky’s Black History and Culture, life for free Blacks was not the same as being free and white. They were required to carry “free” papers which had to be registered for a fee each year, and they could be arrested for “crimes” that only applied to them, such as visiting enslaved people. They were not allowed to defend themselves against attacks by whites.

In Kentucky, people of color did not have the right to vote. Kentucky’s third Constitution of 1850 specifically required all voters to be “white.” It was not until the 15th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution was ratified in 1870, that African American men were given the right to vote — at least according to the Constitution. (Women wouldn’t have that right until 1920.)

The era marked the beginnings of Jim Crow laws which were used throughout the South to reduce the Black vote through stipulations, intimidation, and violence. This would last nearly a century. Some say the effects of this era still exist.2

Juneteenth

Juneteenth recognizes the date June 19, 1865, when the final enforcement of the Emancipation Proclamation was carried out in Texas. In the decades after the Civil War, June 19 became a symbolic date. African Americans in Texas began celebrating Juneteenth as early as 1866, with recognition spreading as they migrated to other communities.

Though Juneteenth was declared a holiday in Kentucky in March 2005, it was not officially celebrated statewide until it became a federal holiday in 2021. It wasn’t until May of 2024 that Gov. Andy Beshear declared Juneteenth a state Executive Branch holiday.

In “The Hidden History of Juneteenth,” Gregory Downs, Professor of History at the University of California, Davis, wrote, “Juneteenth is an important moment in the history of emancipation because it reveals the way that emancipation did not happen all at once or with the stroke of a pen but in a brutal, decades-long fight against slave owners who did not surrender or retreat.”

“Separate but equal”

In 1896, the United States Supreme Court ruled that racial segregation was lawful if “separate but equal” public facilities were available to African American citizens. Restrictive covenants and a segregated education system would follow. Although the Brown v. the Board of Education case of 1954 would result in requiring all public education facilities to desegregate, many remained segregated.

Led mostly by young people in 1961, African Americans in Louisville began demonstrations to end racial discrimination and segregation. By that summer, most of Louisville’s businesses had agreed to desegregate. To learn more about segregation in Kentucky, Tim Talbott’s “Campaign to End Racial Segregation in Louisville” is an excellent read. 3

The 1966 Kentucky Civil Rights Act legally desegregated all public accommodations in the Commonwealth.

Rikiyah recalled a moment sitting in the front row of The Virginia Theater in downtown Somerset when she realized that in the theater’s heyday (then known as the Virginia Cinema), she would not have been permitted to take a seat in the front row based solely on her skin color. She said people of color were made to use a back entrance in the alley to enter the theater, take balcony seats, and were most likely not permitted to use the theater’s restrooms.

If you ask local people of our older generations, they may recall having separate water fountains, separate restrooms, separate entrances, separate everything for people of color. Dunbar School was an all-Black school located in Somerset that operated during the era of segregated education. It closed in 1964, two years ahead of the Kentucky Civil Rights Act.

Fast forward to a need in 2020

“The Lake Cumberland Diversity Collective started out as the Lake Cumberland Diversity Council,” explained Rikiyah of the group’s formation. “It was an idea that stemmed from a need that myself, Kathy Townsend, and JaKaye Martin saw.”

“We got together during the height of 2020 and there was just a lot going on. There was a lot of confusion, shootings, Black Lives Matter was at an all-time high.” Rikiyah said young people in the region were upset. “There’s not a whole lot of people of color here and so people would come to us a lot and we realized that. People wanted us to help or say something or do something.”

Rikiyah said there was a group of teens who wanted to start a riot since that’s what they saw going on. This was also during the time when Breonna Taylor was shot and killed by Louisville Metro Police on March 13, 2020. There were many protests happening, demanding justice.

Rikiyah said she, Kathy, and JaKaye got together with these young people who had so many questions and asked them what good rioting would do locally. She said they asked the youth what would actually make a difference in their lives as well as the quality of life for people of color who live in our community.

Collectively, they chose to have a peaceful Juneteenth celebration. They called it a “charrette,” which translates as a meeting to attempt to resolve conflicts and map solutions. “Dr. King showed us how and there’s no reason to try to reinvent the wheel so that’s what we did,” Rikiyah said.

“A lot of people didn’t even know what Juneteenth was,” Rikiyah said. So they decided to make the event more about education. “We had people reading poems, old spiritual hymns, and spoken word.”

“I did a speech about my parents because I am a biracial child. My dad is white. My mom is Black. But I don’t look biracial. I look exactly like my mother. But by blood I am both. Growing up there were people who were very confused when they’d see just me and my dad. There’s a lot that comes with growing up that way and my parents were very bold for being a biracial couple where we lived.” Rikiyah said there were people sharing similar stories at that first Somerset Juneteenth event as a way to educate and talk about it, and have open conversations about things people might feel uncomfortable asking.

Rikiyah said they were not sure anyone would show up for the event due to a torrential downpour taking place. To their delight, the event, which took place at the Judicial Plaza downtown, was packed with people carrying umbrellas, wanting to learn more. “The mayor was there, the governor’s office called, the judge, the Chamber of Commerce, just everybody from the community showed up.”

“It was one of the most beautiful things I have seen here,” she recalled. Attendees urged the group to continue the event and not just have a “one and done” thing. That’s when the Lake Cumberland Diversity Council was formed. “We wanted it to be a group of people who had input and background and education for different parts of diversity. We had some of us who were Black, Hispanic, of Asian descent. We had people who were speaking on behalf of the deaf community, and the LBGTQ+ community.”

Rikiyah said great care was taken when creating the group, and how they were presenting their messaging. “We’re trying to effectively reach people, not push an agenda,” she said. They wanted the perception of the organization to be that of an open and safe space where even the most awkward questions could be asked without offense. “You need to come from a place of understanding, kindness, love, and openness when you’re having these conversations with people.”

The organization has since become the Lake Cumberland Diversity Collective. Rikiyah said many of the originating group members have since stepped aside to allow for different leadership.

The Juneteenth event is coordinated with Dr. Elaine Wilson of Somerset Community College. For this event and Black History Month happenings in the area, please follow facebook.com/lakecumberlanddiversitycollective.

“We want to keep that conversation going,” Rikiyah said. “It’s all about the education.” She added that there was an acknowledgment of how quickly things were changing and the council also wanted to help generations stay connected, informed, and aware of different mindsets. Despite continued instances of racism still existing, especially how it affects our youngest generations, Rikiyah said there are people who are really trying to move forward.

“Having conversations, especially about being Black or being African American, or race in general, for me, needs to be brought from a place of education and a place of learning. People have to be willing to give and receive.” She also said the conversations need to be presented in a non-condescending manner.

“I’m not saying we have to focus on the past,” Rikiyah said. “All I’m saying is to acknowledge it. That’s it.” She says we should be able to have conversations about where we’ve been as a community and where we are now.

Wise beyond her years and genuine to who she is, Rikiyah said, “I have been very fortunate to have been raised by parents who have raised me in the mindset of not being so overly concerned with how people look at me, but how I look at myself and other people, and how I treat other people because of that.” For Rikiyah, she wants her color to be seen, and regardless of the perception of what that is, she just wants people of all colors to be respected. “That’s all diversity really is,” she said. “Love it or hate it, I am going to respect you as a human being and that involves you seeing my color.”

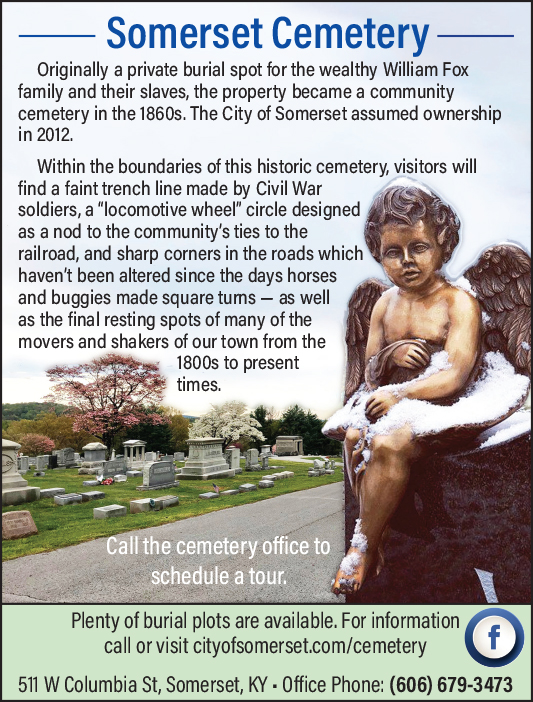

Lake Cumberland Slaves Memorial

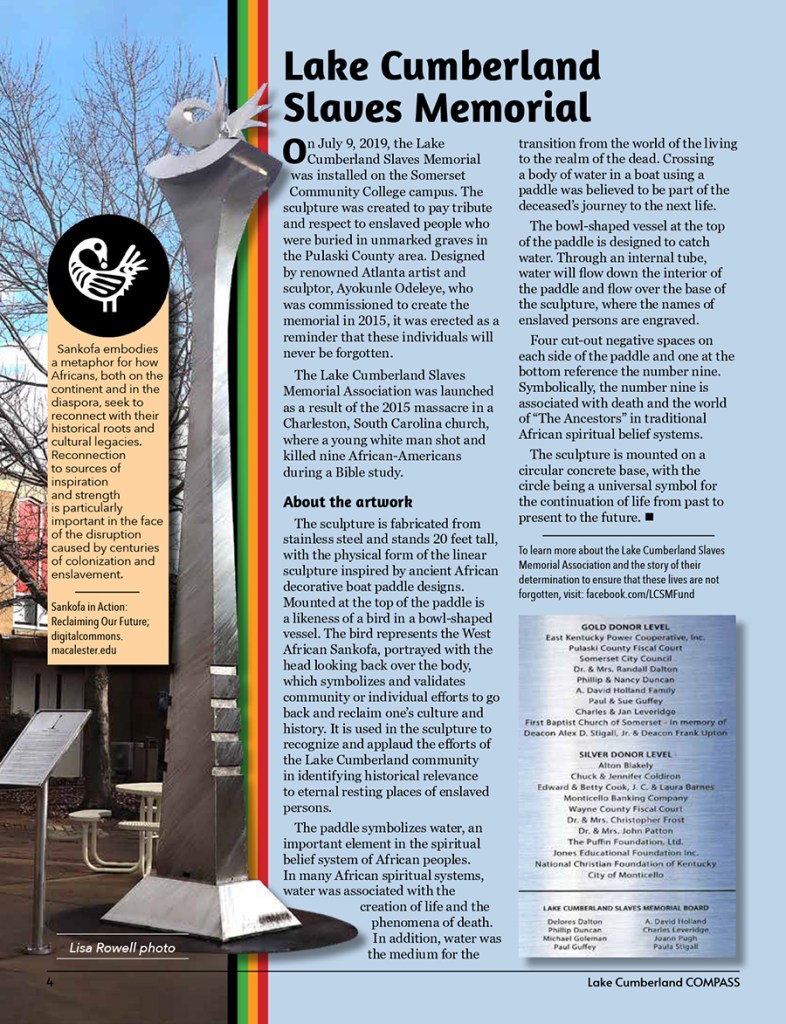

On July 9, 2019, the Lake Cumberland Slaves Memorial was installed on the Somerset Community College campus. The sculpture was created to pay tribute and respect to enslaved people who were buried in unmarked graves in the Pulaski County area. Designed by renowned Atlanta artist and sculptor, Ayokunle Odeleye, who was commissioned to create the memorial in 2015, it was erected as a reminder that these individuals will never be forgotten.

The Lake Cumberland Slaves Memorial Association was launched as a result of the 2015 massacre in a Charleston, South Carolina church, where a young white man shot and killed nine African-Americans during a Bible study.

About the artwork

The sculpture is fabricated from stainless steel and stands 20 feet tall, with the physical form of the linear sculpture inspired by ancient African decorative boat paddle designs. Mounted at the top of the paddle is a likeness of a bird in a bowl-shaped vessel. The bird represents the West African Sankofa, portrayed with the head looking back over the body, which symbolizes and validates community or individual efforts to go back and reclaim one’s culture and history. It is used in the sculpture to recognize and applaud the efforts of the Lake Cumberland community in identifying historical relevance to eternal resting places of enslaved persons.

The paddle symbolizes water, an important element in the spiritual belief system of African peoples. In many African spiritual systems, water was associated with the creation of life and the phenomena of death. In addition, water was the medium for the transition from the world of the living to the realm of the dead. Crossing a body of water in a boat using a paddle was believed to be part of the deceased’s journey to the next life.

The bowl-shaped vessel at the top of the paddle is designed to catch water. Through an internal tube, water will flow down the interior of the paddle and flow over the base of the sculpture, where the names of enslaved persons are engraved.

Four cut-out negative spaces on each side of the paddle and one at the bottom reference the number nine. Symbolically, the number nine is associated with death and the world of “The Ancestors” in traditional African spiritual belief systems.

The sculpture is mounted on a circular concrete base, with the circle being a universal symbol for the continuation of life from past to present to the future. ν

To learn more about the Lake Cumberland Slaves Memorial Association and the story of their determination to ensure that these lives are not forgotten, visit: facebook.com/LCSMFund